Updated

August 08, 2017

| By Bob Fugett ©2017

Offset 3-tuple

Ed Whitney held out three fingers.

The uniform distance between the finger tips formed an almost perfect sideways "W" as they aligned in a straight row.

Ed sat at the apex of two dozen rapt artists circled around him for one of his weekly Saturday morning watercolor classes at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx.

That circle was routinely repeated with different students, many of them already

professional watercolorists, in numerous art centers throughout the United States.

It was during the rare and hallowed time when Ed Whitney was the central seminal force, teaching students who were to become the major American watercolorists of the mid-20th and 21st centuries.

Whitney's teaching was not by accident, and his unparalleled influence was based

on the fact he unwaveringly taught practical use of applied logic in artistic

communication, so those who listened well did exceedingly well.

Using his outwardly stretched fingers, Ed explained an incredibly valuable fundamental element of the deeply innate language of human aesthetic response.

It is a language known to all artists, in all times, in all parts of the earth.

Plus the language is understood without study by virtually every human who ever existed.

For an artist, it is every bit as powerful for communication as it is easy to learn and understand.

And, though the language is not rocket science, it is precise, repeatable, and enduring.

A comprehensive scientific study of this language is called semiotics, but the Whitney classes were not so formal.

When Whitney's fingers were stretched out, he was explaining only the functional application of

just one single morpheme

of the language.

Ed would demonstrate how three evenly spaced fingers are static and boring, but

by offsetting the middle finger the composition is improved, making it more dynamic and interesting.

The photo above shows a similar gesture to how Ed would splay his three fingers

saying that an

offset of elements adds dynamic interest to an otherwise static composition.

This observation of a timeless compositional design-universal describes an aesthetic essence that has stood the test of all

time, surviving all artistic fads ... after fad, after

fad ... always has, and always will.

There are many other compositional universals that are

equally accessible and can be successfully studied with good result.

We will call this basic

semiotic morpheme an offset 3-tuple.

Repeated use of offset 3-tuple helps unify the

organization of Mary Endico's plein air from memory,

Botanical Rain.

The painting is a successful watercolor

that has produced strong and enduring aesthetic responses from a wide range of

art enthusiasts for more than 40 years.

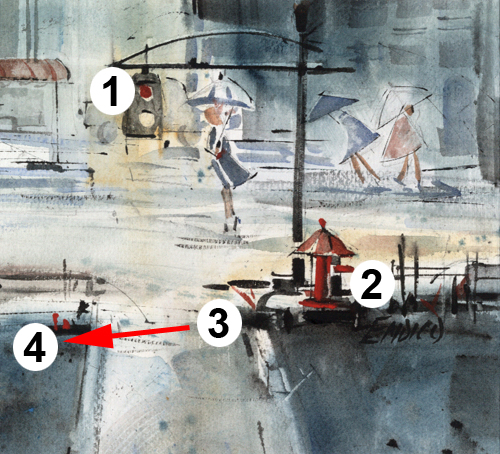

Below is a series of examples pointing out instances

of offset 3-tuple occurring in the watercolor.

Botanical Rain - Mary Endico ©1979

(9" x 10" original watercolor)

Above is the unadorned Botanical Rain watercolor, and

below begins the labeled illustrations of how the three-offset principle was

used throughout.

The examples are ordered here from the easiest to hardest to grasp, so the

first one above is based on the most prominent human interest element, the

three people struggling with umbrellas; make note that having the central figure

pulled forward in the perspective reinforces the separation of the 3-tuple

interest grouping.

The three element grouping above follows a diagonal line

from the traffic light, through the central figure, ending at the hydrant; this

grouping is assisted by the repetition of the color red which leads the

viewer's eye in a loop.

The three horizontal points above are somewhat more

difficult to recognize as being an offset 3-tuple, but the larger dark shape of item 3 has more weight than

does the more narrow item 1 due to its greater surface area, while the

similarly sized but lighter passage of item 2 is a

negative space that allows the eye to easily flow through item 2 either

to 1 or 3; thus the 1, 2, 3 offset is enhanced by alterations of size and

color and can be read as flowing either right or left.

The three points above require an ever more advanced

understanding because they rely mostly on surface area alone; plus they

require a mental calisthenic in order to follow the line of interest through

item 2 going up the right angle to gain a resting point at 3; only then comes

the realization that the three together are forming a gestalt offset.

In the example above, the level of abstraction has increased

again, and the 3-tuple is now based on color, as the red highlight of the traffic light (1) is

repeated diagonally by the red hydrant (2) then offset to the sprouted red

grass at its base (3) while the weight and importance of the red grass is

buttressed by the bonus red weed

(4) across the negative space of the road.

Here the hydrant is enlarged in order to show the

offset red areas at its top (the hand example has been copied and rotated on

two axes to aid recognition); also another three-offset is found on the vertical

axis and numbered accordingly.

The hydrant image provides a convenient transition for moving

our discussion

of offset 3-tuple to examples of how this basic semiotic design universal

(an aesthetic response morpheme) is also used in Mary's

haute conduite non-objective abstracts.

|